Henry Hershey, 1829-1904

Born January 4, 1829 at The Homestead, Henry Hershey was the oldest of seven children, six of whom survived to adulthood. His parents were Jacob and Nancy (Hershey) Hershey. This is the family roster: Henry (1829-1904), Joseph (1830-1855), Elizabeth (1832-1903), Christian (1836- ? ), Jacob (1938-1887), and Elias (1841-1925). Little Isaac (1846-1848) died before he was two years old.

Henry had an alert inquiring mind and loved learning and books. Henry’s father discouraged his desire for a formal education, believing a man should learn to support himself. Henry tried to please both his father and himself, with the result that he disappointed both. Henry was an eternal optimist, as well as creative, curious and self-confident.

When Henry was twenty-one years old, he worked as a tenant on his father’s farm while attending night school at the same time. This experience reinforced his love of books and reading, but did not provide him with the intellectual grounding necessary for the writer’s career he hoped to enter. He accepted his father’s plan for him and worked on the family farm; but his heart was not in it, and he drifted into the habit of dreaming. To the end of his days he seemed incapable of concentration, and the failure he made of farming was projected into everything else he undertook.

Henry Hershey was 27 years old when he married Veronica “Fanny” Snavely on January 15, 1856. Neither one was a member of the Mennonite Church so they were married at the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity in Lancaster by Rev. Gottlob Frederick Krotel.

Things went well enough with the young couple at the start. Henry was handsome, tall, well-dressed, courteous in manner, an engaging talker. She was proud of him and he of her. She was a pleasant little woman, neat and quick about the house, a good housekeeper, careful of the pennies, not without ambition. She had a little money of her own, and when her husband’s business ventures went astray she was able at first to help him. Their first child, Milton Snavely Hershey, was born at his grandfather’s farmhouse (The Homestead) on September 13, 1857. A second child, a daughter named Sarena, was born on April 12, 1862.

The early years of Henry and Fanny Hershey’s marriage were filled with frequent moves as Henry followed one dream after another. Each move carried them further into poverty and rough circumstances. Fanny soon realized that her husband would not achieve the kind of success the Snavelys and Hersheys respected. To Mennonites money and property meant more than mere worldly convenience. Financial success was a reflection of Divine blessing. Henry’s failure to achieve financial security pushed the couple apart. Finding that security became Fanny’s main objective, and in pursuing it she drifted more and more apart from him. It was only the birth of their children that held them together.

They moved from the Homestead to another home owned by Henry’s father. Pursuing the oil boom in western Pennsylvania, Henry moved his family to a shack near Oil City, PA. In the midst of these moves, a daughter, Sarena, was born in 1862.In 1866, then, Henry Hershey moved with his family to a forty-four acre farm, about half a mile from Nine Points and some fifteen miles south of Lancaster city. Nine Points was no more than a crossroads. The farmland was poor and the house was a small log structure. Tragedy came in 1867 when Sarena died of scarlet fever. Her death created a permanent break between the couple. Henry Hershey began spending longer periods of time apart from his family. Henry Hershey seemed to pop in and out of his family’s lives, often attempting to solicit their support of his latest business ventures. His input often had a dramatic impact on his son.

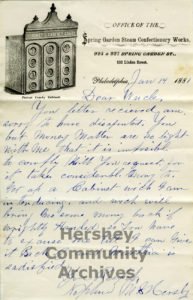

When Milton Hershey was working at his first business venture in Philadelphia, Henry’s idea for a new Candy Cabinet, created financial stress for his son. Milton purchased the patent for his father’s cabinets, causing his own candy business to go bankrupt. Henry’s glowing letters from Colorado led his son to travel to Denver seeking a new opportunity to establish a business. As was often the case with Henry Hershey, the timing was bad. By the time Milton Hershey arriving, Denver was entering into a financial depression. It was because of Henry Hershey’s encouragement that Milton Hershey went to New York City to start his second business venture

No city could hold onto Henry Hershey long. There is evidence of him in New York, Chicago, Colorado and points in-between over the course of several years. From the evidence, Henry lived in impoverished conditions, trying his hand at silver mining, portraiture, day labor, candy making and anything else he could try his hand.

While Henry was living the life of a wanderer, Fanny Hershey listed herself as a widow in the City Directory. After Milton Hershey achieved financial success with first the Lancaster Caramel Company and later Hershey Chocolate Company, Milton took care of his father, sending him money each month. In 1897 Milton Hershey bought back the Hershey Homestead and made plans to bring his father home.

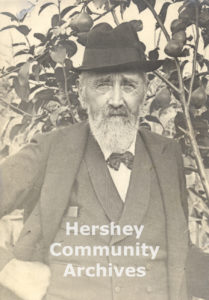

Henry arrived sometime in March or April 1898, dressed unexpectedly in a Prince Albert frock coat (a little faded), with a silk hat, and a cane. But in two minutes he had won all hearts, and during the next few days captivated the whole neighborhood–except, that is, certain persons who tried to dispute with him on religious topics, and found themselves beaten because of his superior knowledge of the Bible. Rumor gained ground that he had once been a saddle-bag preacher.

Until his death in 1904, Henry relished his son’s success. During his last years he often was seen riding about in a horse and buggy dressed in a frock coat and silk hat. He spent his days reading, discussing ideas and conducting agricultural experiments.

Derry Township was soon divided into two camps: those who were for and those who were against Henry Hershey. He had all the children with him. He had a wonderful way with youngsters, turning everything in their presence into fun. He captured also most of their elders, whom he laughed with and helped in a thousand ways. He took neighbors with him in the horse and buggy to church camp meetings and picnics. He went round to the schools, giving talks to the children about everything under the sun from fossils and caves and the history of religion to modern labor problems and the future of America. When Miss Edna Erb was taken sick at school he drove out and brought her home. If neighbors were moving, Henry Hershey picked up their children, gathered their clocks and other small furniture in the wagon, and brought them along. The Horseshoe Pike (Route 322) was his post road: from Hockersville, where he got his mail, to Amos Brandt’s hardware store in Campbelltown where he picked up mechanical aids for the inventions he used to bring down out of his room in the evenings to show his friends.

Henry Hershey said that the years he spent at the Homestead after 1898 were the happiest of his life. Milton gave him a good home, money to spend, a black horse and carriage to drive out in, and land on which to experiment with shade trees, imported fruit trees, a new trout pond, chickens, agricultural implements, vegetables, telephones, and alfalfa. In the comfort and security of these surroundings, Henry Hershey’s mind warmed and expanded. He was soon Derry Township’s most talked of, as well as talkative, citizen. He subscribed to the Philadelphia North American and kept up with developments in politics and industry. His conversation ranged over the whole earth.

The center of Henry’s life was the library, which Milton had provided for him in his downstairs sitting room at the northwest corner of the Homestead. In it were books of Henry’s choice, a wall full of them, piled so high with history, religion, and nature study that Henry had to climb up a stepladder on rubber rollers when he wanted anything from the top shelf. There was a large wall map, beautifully printed in clear, bold letters.

Milton and his father were close to each other. When Milton was traveling between the Homestead and Lancaster by train, his father used to drive him to the station in Elizabethtown. Milton discussed his plans for a new town. It was through Henry that the first hint of these reached the public.

It came about in this way. Henry Hershey enjoyed taking part in the meetings of the adult Literary Society held at the Greiner School (at the corner of Chocolate and Cocoa Avenues), under the chairmanship of the school’s teacher, Solomon Balsbaugh. One evening, during a session of impromptu speeches, Henry Hershey drew this topic: “Predict the future of this place twenty-five years hence.”

“I can see him well,” says Solomon Balsbaugh. “He threw his head up and round, and walked about the platform. His first statement was, ‘Twenty-five years from now, this will be a smart town of several thousand inhabitants.’ This was followed by ironic applause–clapping and stamping. ‘Trolley cars will extend in all directions. The place will be dotted by skyscrapers.’ There was laughing and howling.” Not a word of what he said was believed.

The years brought no diminution of Henry’s vivacity. Up to the end he was experimenting with plants and machines and means of beautifying the place for his son. It was Henry Hershey who introduced alfalfa to these parts. Homestead workers Hoffer Bowman, Harry Tinney, and Monroe Hershey made a hotbed for him, eighteen feet long by six feet wide, and Tinney white-washed the fence around it. Henry sowed seed he had ordered from California. He persuaded Will Erb to plant an acre or two. And that is how alfalfa came to Derry Township.

He had a fenced-in vegetable garden in front of the Homestead, where he raised prize vegetables for the New York market. He planted poplars round the Homestead and along the Horseshoe Pike as far as Abe Flower’s place. Little Esther Grubb (now Mrs. Edwin Laudermilch) wanted to see how he did it, and so she rode with him while he dropped the young trees from the wagon into holes already prepared. He bought lumber from John Early of Palmyra and made a small greenhouse. Almost every day he was down at Amos Brant’s Hardware Store in Campbelltown, looking for gadgets to fill out his inventions B it might be a model silo, a hay rake, or a burglar alarm for the barn.

He was always looking into the future. To the Schlesser girls in 1898 he said: “I won’t live to see the day when there will be horseless carriages and flying machines, but you will.” He laughed, and added: “There will be all sorts of new implements. There will be one machine that will cut the grain, thresh the grain, and make it into flour and pancakes.”

Henry was full of fun. When Milton substituted springless iron beds at the Homestead for the rope beds the farm hands had been accustomed to, Henry made sport of the complaint he overheard that the iron would attract lightning. One day Henry met Harry Tinney coming out of the creamery, and slapped him on the back.

“Now let it thunder and lighten,” said Henry. “It isn’t going to hit me.”

“What have you done, Dad?”

“Why, I’ve set a glass of water under my bed. Water is a good conductor.”

Henry was free with the men, but they respected him. He wrestled with the young fellows and joined them at work in the fields or the orchard. He looked a little conspicuous, for he often worked in his best clothes. On going away from home at any time, he always wore his Prince Albert coat, in which he looked very handsome. On returning, he would not bother to change it as he went out to water the orchard, just wrapping the hose round his shoulder.

Henry lived to see the foundations dug for the chocolate factory and watched as the walls went up, but he did not live to see the town whose rise he had predicted.

One day in February, 1904, Solomon Balsbaugh met Henry Hershey at Hockersville, and saw him strike his chest and say, “I’m going to live to be a hundred.”

A day or two later, on the morning of February 18, 1904, Henry Hershey drove to Erb’s Store at Hockersville. In the afternoon he called on Dr. Martin Hershey at Derry Church. He had not been feeling well for some time, but his friends were not aware of it. He and Dr. Hershey chatted for a while in the doctor’s office. Henry talked about Milton. “Yes,” he said, “I’m very glad Milton is married. You know, he married a working girl. It is very happy all round.”

When Henry was ready to go, they found the ground blanketed with snow. It was one of those wet, heavy, exasperating snowfalls that make February in southern Pennsylvania the most disappointing month of the year. Dr. Hershey put on his coat to drive Henry home: but when they got to the stable they found the carriage not available. It did not matter, Henry said; He would not mind walking. It was a difficult walk, the snow growing deeper every minute. Henry found himself quickly tired. Fortunately Christopher Moyer came along in his spring wagon and gave Henry a lift to where the road from Derry Church passed near the Hershey Homestead. There Henry got out and tried to walk the rest of the way home, but found something had gone wrong with his legs. They refused to obey him. As he staggered up the lane by the boiler house, Harry Tinney, fixing the fires for the night, happened to look out of the window and saw him reel against the door. Just then Albert Snavely, the timekeeper, came in and said, “Pap Hershey is standing here by the building. There’s something wrong. We will have to lead him in.”

Albert Snavely and Hoffer Bowman went out to help him, while Tinney remained to fix the fires.

“I remember him standing at the corner of the building,” said Hoffer Bowman. “His lips were getting blue. As we led him in, he said, ‘I’m perfectly paralyzed.’ Those were the last words I heard from him.”

They laid him on a sofa near the door. Fanny Hershey, who was visiting at the Homestead, was with him at once. Hoffer Bowman phoned to Dr. Martin Hershey, but it was all over in five minutes.

In the Harrisburg Telegraph, Saturday, February 20, 1904, appeared this notice:

Henry H. Hershey died of heart failure very suddenly at his home near Derry Church, on Thursday evening, at 5 o’clock. He had been ailing for some time. Deceased was born 78 [actually 75] years ago at or near the place he died. He spent part of his life in Chicago, part in New York and Lancaster was closely identified with his son and only child, Mr. Milton S. Hershey, in the manufacture of chocolate caramels and in accumulated a great amount of wealth. He was greatly interested in all kinds of agricultural experiments and developments and had a fine exhibit at the Middletown fair last summer. He is survived by one brother, Rev. Elias Hershey, a prominent minister in the Mennonite Church, residing near Lancaster, also by a wife, who was the only relative at his bedside when he died, for the son is in Florida and cannot reach home before today, after which arrangements will be made for the funeral.

The Reverend Jacob S. Lehman from Chambersburg, a minister of the Reformed Mennonite Church, preached the funeral sermon. Henry Hershey was buried in the cemetery beside the Hershey Meeting House.

Milton, looking down at his father’s grave, was heard to say, “I wonder if Dad has made up his mind about the future life.”

For Fanny Hershey there was one thing more to be done to make the reconciliation with Henry perfect. She collected all his books, had them brought out to the boiler house, and burned them.