Catherine “Kitty” Sweeney Hershey, 1871-1915

Additional photographs of Catherine Hershey can be found at the Archives’ Flickr site: http://www.flickr.com/photos/26307193@N02/sets/

Picture it. A young, working-class girl from western New York state meets a rich Lancaster, PA businessman fourteen years her senior at the turn of the 20th century. They fall in love, get married, and settle in the rich farmlands of central Pennsylvania. His company expands and eventually becomes world-famous; she enjoys only a few early years of his success due to a debilitating illness that inevitably shortens her life. He goes on to fame and fortune and endures the last thirty years of his life without the one that made him smile. Sounds like an enchanting romance novel. The great thing about this story though, is that it is true!

Catherine Elizabeth Sweeney, or “Kitty” as her family called her, was born on July 6, 1871 in Jamestown, New York. Located near the northwest border of Pennsylvania, Jamestown was originally a lumbering community that was home to many different immigrant groups. During the late 19th century, Jamestown emerged as a prominent center of commerce and trade and in 1886 was incorporated as a city. Catherine was born at the beginning of Jamestown’s renaissance.

As the oldest daughter of Irish immigrant parents, Michael William Sweeney of Cork and Catherine Elizabeth Maloney of County Clare, Catherine was the second of four children. She was baptized on July 16, 1871 in the Church of Saints Peters & Paul, as were her three siblings: William Miles, born in April 1867; Lougoria Agnes, born July 29, 1874; and Mary Frances (Maime), born March 15, 1881.

Kitty’s formative years were happy but hard. Family members were known for their sense of humor. Money was scarce and the opportunities for diversions few. Kitty attended Jamestown High School but did not graduate, preferring instead to leave in 1888 during her senior year and work in a shop. As a shop girl, Kitty worked long hours, six days a week. She honed her service skills and used a bubbly personality to entice customers when she was a clerk in a Jamestown jewelry store. Her “career” was Kitty’s way of contributing to her family’s upkeep, while still getting what she wanted. Working in retail did not carry the stigma of domestic service, a field many of her Irish- immigrant friends entered. A store offered variety and social interaction, personal satisfaction in making other people’s wishes come true, an opportunity to surround yourself with beauty (especially in a jewelry store) and the chance to learn about material goods.

As a working girl, there were opportunities to socialize with friends. A popular destination was the local soda fountain. Friends would congregate there on their day off or in the evenings. In the 1890s she frequented A.D. Work’s Confectionery, and what transpired there would change her life forever.

Milton S. Hershey was a middle-aged bachelor with an eye for the exceptional. A successful confectioner by the 1890s, his early working years had been marked by failure. He finally found success with his Lancaster Caramel Company. Business required he travel to promote his products and acquire new orders. In 1897, he was passing through western New York state on his way to Chicago and called on A.D. Work’s Confectionery in Jamestown. There he met Catherine Elizabeth Sweeney.

Kitty’s sister, Agnes Sweeney Smith, recalled their meeting in a 1950s interview: “She was not selling candy. The girls used to congregate there and fuss around. So Mr. Hershey was in there with Mr. [William F.R.] Murrie, and of course the girls introduced him to my sister.” Thereafter Jamestown was a constant on Milton Hershey’s travel docket and Kitty was a constant on his mind.

Given Catherine’s outgoing personality, there is no doubt that she was good at making people notice her. Catherine’s demeanor captured Milton’s attention and during their year-long courtship she had enough time to think about her suitor and his possible proposal. Communications between the traveling entrepreneur and the young shop girl were sometimes difficult; as Agnes remembers, “He was the poorest hand to write a letter. He would send telegrams to my sister rather than write a letter. She used to get so provoked. She said, ‘You never saw anyone who disliked to write letters as he did.'”

After beginning their courtship, Kitty moved to New York City and worked in the ribbon section of Altman’s Department Store. She didn’t work there long, but she was there when the two decided to get married. The wedding ceremony took place Wednesday, May 25, 1898, in the rectory of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Assistant Rector Reverend Thomas F. Murphy performed the service, with Francis Foley and Alice McKenna serving as witnesses.

Kitty now had a huge hurdle to overcome, marrying Milton Hershey without any warning to family or friends. The Lancaster Caramel Company was a major industry in Lancaster and Milton Hershey was considered one of the town’s leading citizens. Milton Hershey’s cousin, Lila Snavely recalled, “These people [in Lancaster] were surprised at his marriage–because he had married [her], and also because he had married at all. Everybody thought he was roped in, but he really liked her.”

In addition to the community’s reaction, Kitty had to contend with Milton Hershey’s mother. A strict Mennonite, Fanny Hershey dressed plainly and accepted with reluctance the changes that came with her son’s unexpected marriage. Fanny Hershey was completely shocked when Milton gave her the news. He thought his mother might disapprove of his marrying a girl like Kitty (for social as well as religious reasons), but he did not care.

The marriage was good for both Kitty and Milton. Milton Hershey’s stern Mennonite upbringing and years of focusing his attention on building a successful business had limited his experience with pleasurable activities. Kitty, a woman of limited financial means, had a lively spirit and a warm and outgoing personality. They provided each other with the things they lacked and enhanced their separate identities. She fussed over him and referred to him as “my little Dutchman” and he doted on her. Throughout their marriage he never failed to bring her a daily arrangement of fresh flowers.

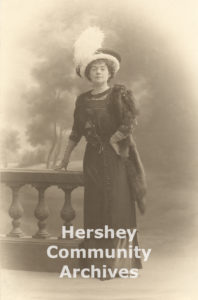

Kitty was a beautiful woman, graceful and elegant. Her hair was auburn-chestnut, her figure small and refined and her personality was bubbly and gay. Kitty was the Gibson Girl personified. She was a gregarious woman and enjoyed the company of friends and like minded individuals. Her beauty and openness attracted others to her.

The Hersheys began their marriage happily, looking forward to their life together. As was common for husbands of this period, Milton looked upon her as a dependent child that needed attention and care. She was his excuse to take a break from his all encompassing work. If Milton stayed away too long on a business trip, Kitty would phone his associates and instruct them to buy a ticket and send him home.

Shortly after returning to Lancaster after the wedding, it was clear that Kitty and her mother-in-law, Fanny Hershey, suffered personality differences. Mother Hershey commented on her new daughter-in-law’s “pride and vanity.” At Fanny’s request, in September 1898 Milton Hershey resolved the conflict by buying his mother a new residence at 143 South Duke Street, Lancaster.

If Fanny Hershey frowned upon her son’s choice for a wife, Kitty’s arrival delighted Milton Hershey’s father, Henry. In 1898, he was residing at the Homestead (Milton’s birthplace), located in Derry Township. When Kitty visited the Homestead she could count on her father-in-law for a smile and compassion. While she enjoyed Lancaster and the friends they had there, the Homestead was the place where Kitty could unwind and be herself. She loved the country and valued her time away from “society.”

The million dollar sale of Milton Hershey’s Lancaster Caramel Company to the American Caramel Company in 1900 changed his direction. Refocusing his energies on the Hershey Chocolate Company resulted in Milton Hershey developing a new approach to business. He needed a new factory for his booming business. Instead of building a new factory in an established city, Milton Hershey envisioned building a model town from scratch to support his new chocolate factory. He chose Derry Township with its rail line, adequate fresh water sources and abundant dairy farms as the location for his chocolate factory. The factory was completed in 1905, and the town of Hershey began to take shape.

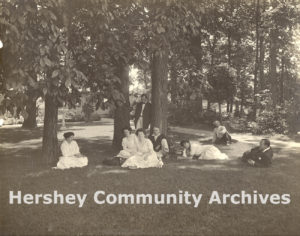

When Kitty wasn’t entertaining in Lancaster or retreating to the Homestead, she was traveling. Going places and meeting new people was one of her favorite pastimes. She and Milton spent most of their married life touring the world. In the beginning they went to places where Milton could learn about chocolate. In later years the Hersheys’ travels became a quest to find some relief from the illness that tormented Kitty during the last ten years of her life.

The first signs of Kitty’s illness appeared three years after her marriage. In 1902, Kitty complained to her friend Lila Snavely about a lack of control over her body, “Oh, Lila, I must go round with a card tag round my neck. I fell over in Broad Street Station [Philadelphia].” Identified as “locomotor ataxia,” the precise symptoms and consequences were a mystery and a modern equivalent is not known. It is likely that she had some sort of debilitating muscular or neurological disease, because as the years went on it continued to progress and affect her mobility.

Kitty did not let her illness deter her from her duties and responsibilities as the wife of Milton S. Hershey. She supervised the construction and landscaping of their new home in Hershey. High Point was completed in 1908. It was furnished with many of the items bought on trips to New York City and abroad. High Point’s foyer housed the large cut-glass torchere Milton had first seen at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Kitty oversaw the interior design for their home, selecting vibrant hues of blue and green for the guest rooms. Milton’s room was gold with blue carpet and Kitty’s was done in pink tones.

High Point was not ostentatious and definitely did not reflect millionaire taste of the time. The construction, furnishings and landscaping of the Mansion may have cost as much as $100,000. In comparison, George Vanderbilt spent an estimated $10 million for his 250-room mansion, Biltmore, situated on 125,000 acres in Asheville, North Carolina. Biltmore had a staff of 90. High Point was maintained by 3 or 4 servants.

Kitty was largely responsible for High Point’s landscaping. She personally supervised the planting of the shrubbery around the Mansion and the big lawn east of the factory. Mother Hershey thought flowers were frivolous decoration, but Kitty saw them as a way to enliven the world around her.

One of Catherine and Milton’s greatest disappointments was that they had no children. The couple had lots of love and money to give, and they decided that if they could not support children of their own, they would become the benefactors of those children that needed help. On November 19, 1909, Milton and Catherine Hershey signed the Deed of Trust establishing the Hershey Industrial School (now Milton Hershey School). Milton Hershey would always say that the School was “Kitty’s Idea.”

If there is one thing that can be said about Catherine Sweeney Hershey, it is that, despite her illness, she never stopped living. Even when it became very difficult for her to walk (about 1912), she structured her life to avoid embarrassing friends. A contemporary, Mrs. Ezra Hershey, remembered: “She suffered from a kind of creeping paralysis, but she was very plucky and never made you feel uncomfortable about it. She loved to go and to dress. She loved gaiety. She never complained a bit about her illness.”

Milton and Kitty traveled extensively, in the United States and abroad. Kitty especially enjoyed traveling because she could let down her guard. At home everyone knew of her condition and watched her carefully. She did not feel free to deal with her pain.

When the doctors had basically given up on her, Kitty turned to Christian Science as a means of distraction, comfort and support. Members of this belief system thought that “evil in general and physical illness in particular could be overcome through prayer and a deeper understanding of God.”

While on their year and a half long trip to Europe (1911-1913) Kitty could still walk, but she had trouble keeping her balance and always held on to a companion’s arm. Once back in Hershey her condition continued to decline. Finding some relief with sea air, she spent increasing amounts of time in Atlantic City, New Jersey. By the end of 1914 she was almost completely paralyzed, and yet she continued to study Christian Science. Despite her outward appearance, she knew what was happening to her body.

Kitty and Milton were at Atlantic City in March 1915 when he was called away on business. Kitty made arrangements to return to Hershey. She had a new nurse drive her in a convertible. The numbness in her limbs made Kitty oblivious to heat and cold, and she insisted on riding with the top down. The day was cold and raw, and Kitty’s condition deteriorated with every mile. Becoming too ill to continue the trip, they stopped at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia and Milton was contacted. Kitty had pneumonia.

Milton Hershey hurried to Philadelphia, arriving that same afternoon, Thursday, March 25, 1915. After greeting him, Kitty requested a glass of champagne which her husband went personally to procure for her. She had died by the time he returned. Milton had not realized the precariousness of his wife’s health. True to form, Kitty had known how ill she was, but had not told anyone, not even Milton, about it.

The funeral mass was said by Reverend Francis J. Clark on Saturday, March 27; Milton Hershey gave his employees the day off and provided a free train ticket to Philadelphia so they could attend the service. Internment was at the West Laurel Hill Receiving Vault in Philadelphia. The body remained there for four years until the Hershey Cemetery was established and the body could be moved.

Milton Hershey never remarried. He spent the next thirty years expanding his company and the Milton Hershey School. He was very careful after he became a widower. He said, “I am very nice to little children and real old ladies, but nothing in between.” Until his death he carried her picture with him everywhere he went.

Source: “The Inspiration for Sweet Success: A Portrait of Catherine S. Hershey, Wife of Milton S. Hershey” by Deborah B. Wescott. Masters thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 1998.